If you’re planning a trip to Istanbul, don’t leave your airport transportation up to chance. When you book a shuttle ahead of time, you can skip the stress and start your vacation off right.

We provide safe and comfortable transfer from any location in Istanbul to any location in Turkey. Istanbul Airports transfers provided by Istanbul Elite Transfer are unlike any typical Istanbul taxi or shuttle services. Using a taxi service, it is highly possible that you will find the taxi unclean, uncomfortable, unsafe and with expensive prices. Our operational philosophy is to provide safe and comfortable transfer without having any hidden costs. We do not charge any additional payment due to flight delay or traffic congestion. It is also diffucult and exhausting to get to any location by metro, by airport shuttles or by any other public transportations. Using our services will make your stay comfortable and will guarantee your piece of mind.

At IstanbulEliteTransfer, we offer a variety of flexible transportation options for any location in Istanbul, so you can ride your way. If you need any ride in Istanbul you can count on, we can help.

We are ready to shuttle you to where you want to go. From Hotel to Airport, from Sea Port to Hotel. Book a valuable transportation service today.

About Istanbul

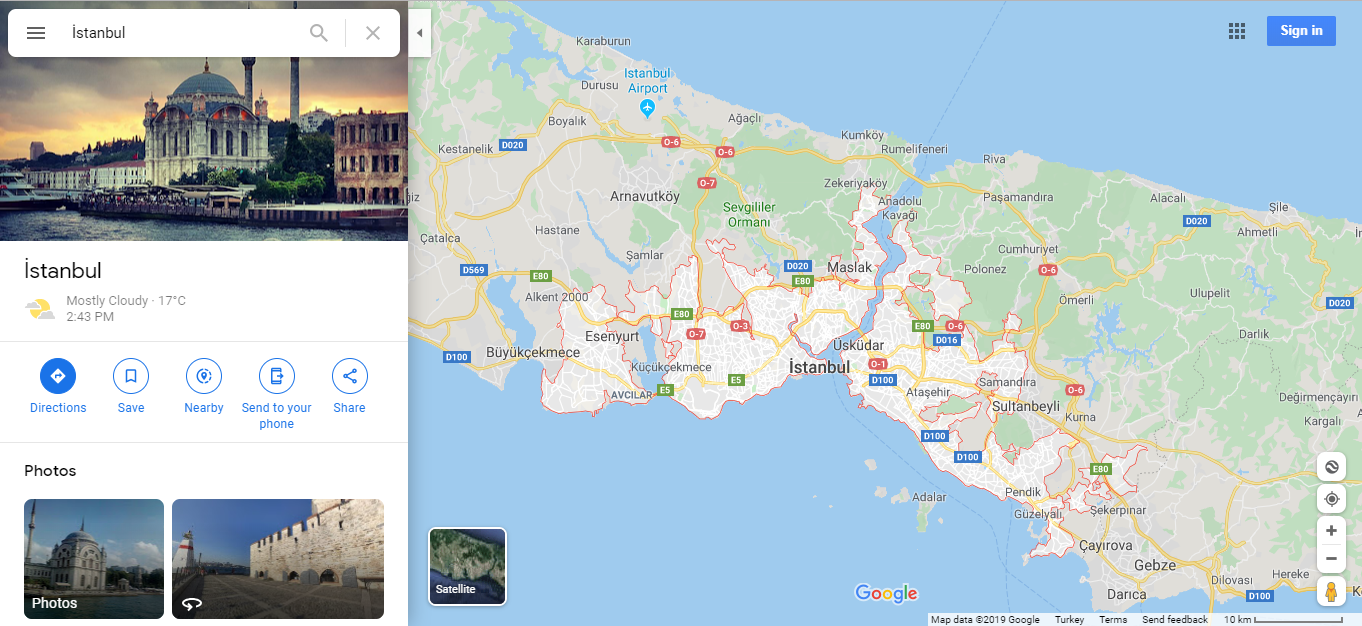

Istanbul (/ˌɪstænˈbʊl/,[8][9] also US: /ˈɪstænbʊl/; Turkish: İstanbul [isˈtanbuɫ] (![]() listen)), formerly known as Byzantium, Constantinople, and New Rome, is the most populous city in Turkey and the country’s economic, cultural and historic center. Istanbul is a transcontinental city in Eurasia, straddling the Bosporus strait (which separates Europe and Asia) between the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea. Its commercial and historical center lies on the European side and about a third of its population lives in suburbs on the Asian side of the Bosporus.[10] With a total population of around 15 million residents in its metropolitan area,[3] Istanbul is one of the world’s most populous cities, ranking as the world’s fourth largest city proper and the largest European city. The city is the administrative center of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (coterminous with Istanbul Province).

listen)), formerly known as Byzantium, Constantinople, and New Rome, is the most populous city in Turkey and the country’s economic, cultural and historic center. Istanbul is a transcontinental city in Eurasia, straddling the Bosporus strait (which separates Europe and Asia) between the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea. Its commercial and historical center lies on the European side and about a third of its population lives in suburbs on the Asian side of the Bosporus.[10] With a total population of around 15 million residents in its metropolitan area,[3] Istanbul is one of the world’s most populous cities, ranking as the world’s fourth largest city proper and the largest European city. The city is the administrative center of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (coterminous with Istanbul Province).

Founded under the name of Byzantion (Βυζάντιον) on the Sarayburnu promontory around 660 BCE,[11] the city grew in size and influence, becoming one of the most important cities in history. After its reestablishment as Constantinople in 330 CE,[12] it served as an imperial capital for almost 16 centuries, during the Roman/Byzantine (330–1204), Latin (1204–1261), Palaiologos Byzantine (1261–1453) and Ottoman (1453–1922) empires.[13] It was instrumental in the advancement of Christianity during Roman and Byzantine times, before the Ottomans conquered the city in 1453 CE and transformed it into an Islamic stronghold and the seat of the Ottoman Caliphate.[14] Under the name Constantinople it was the Ottoman capital until 1923. The capital was then moved to Ankara and the city was renamed Istanbul.

The city held the strategic position between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. It was also on the historic Silk Road.[15] It controlled rail networks between the Balkans and the Middle East, and was the only sea route between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. In 1923, after the Turkish War of Independence, Ankara was chosen as the new Turkish capital, and the city’s name was changed to Istanbul. Nevertheless, the city maintained its prominence in geopolitical and cultural affairs. The population of the city has increased tenfold since the 1950s, as migrants from across Anatolia have moved in and city limits have expanded to accommodate them.[16][17] Arts, music, film, and cultural festivals were established towards the end of the 20th century and continue to be hosted by the city today. Infrastructure improvements have produced a complex transportation network in the city.

Over 12 million foreign visitors came to Istanbul in 2015, five years after it was named a European Capital of Culture, making the city the world’s fifth most popular tourist destination.[18] The city’s biggest attraction is its historic center, partially listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and its cultural and entertainment hub is across the city’s natural harbor, the Golden Horn, in the Beyoğlu district. Considered a global city,[19] It hosts the headquarters of many Turkish companies and media outlets and accounts for more than a quarter of the country’s gross domestic product.[20] Hoping to capitalize on its revitalization and rapid expansion, Istanbul has bid for the Summer Olympics five times in twenty years.[21]

Toponymy

The first known name of the city is Byzantium (Greek: Βυζάντιον, Byzántion), the name given to it at its foundation by Megarean colonists around 660 BCE.[22] The name is thought to be derived from a personal name, Byzas. Ancient Greek tradition refers to a legendary king of that name as the leader of the Greek colonists. Modern scholars have also hypothesized that the name of Byzas was of local Thracian or Illyrian origin and hence predated the Megarean settlement.[23]

After Constantine the Great made it the new eastern capital of the Roman Empire in 330 CE, the city became widely known as Constantinople, which, as the Latinized form of „Κωνσταντινούπολις“ (Konstantinoúpolis), means the „City of Constantine“.[22] He also attempted to promote the name „Nova Roma“ and its Greek version „Νέα Ῥώμη“ Nea Romē (New Rome), but this did not enter widespread usage.[24] Constantinople remained the most common name for the city in the West until the establishment of the Turkish Republic, which urged other countries to use Istanbul.[25][26] Kostantiniyye (Ottoman Turkish: قسطنطينيه) and Be Makam-e Qonstantiniyyah al-Mahmiyyah (meaning „the Protected Location of Constantinople“) and İstanbul were the names used alternatively by the Ottomans during their rule.[27] Although historically accurate, the use of Constantinople to refer to the city during the Ottoman period is, as of 2009, often considered by Turks to be „politically incorrect„.[28]

By the 19th century, the city had acquired other names used by either foreigners or Turks. Europeans used Constantinople to refer to the whole of the city, but used the name Stamboul—as the Turks also did—to describe the walled peninsula between the Golden Horn and the Sea of Marmara.[28] Pera (from the Greek word for „across“) was used to describe the area between the Golden Horn and the Bosphorus, but Turks also used the name Beyoğlu (today the official name for one of the city’s constituent districts).[29]

The name İstanbul (Turkish pronunciation: [isˈtanbuɫ] (![]() listen), colloquially [ɯsˈtambuɫ]) is commonly held to derive from the Medieval Greek phrase „εἰς τὴν Πόλιν„ (pronounced [is tim ˈbolin]), which means „to the city“[30] and is how Constantinople was referred to by the local Greeks. This reflected its status as the only major city in the vicinity. The importance of Constantinople in the Ottoman world was also reflected by its Ottoman name ‚Der Saadet‘ meaning the ‚gate to Prosperity‘ in Ottoman. An alternative view is that the name evolved directly from the name Constantinople, with the first and third syllables dropped.[22] A Turkish folk etymology traces the name to Islam bol „plenty of Islam“[31] because the city was called Islambol („plenty of Islam“) or Islambul („find Islam“) as the capital of the Islamic Ottoman Empire. It is first attested shortly after the conquest, and its invention was ascribed by some contemporary writers to Sultan Mehmed II himself.[32] Some Ottoman sources of the 17th century, such as Evliya Çelebi, describe it as the common Turkish name of the time; between the late 17th and late 18th centuries, it was also in official use. The first use of the word „Islambol“ on coinage was in 1703 (1115 AH) during the reign of Sultan Ahmed III.[33]

listen), colloquially [ɯsˈtambuɫ]) is commonly held to derive from the Medieval Greek phrase „εἰς τὴν Πόλιν„ (pronounced [is tim ˈbolin]), which means „to the city“[30] and is how Constantinople was referred to by the local Greeks. This reflected its status as the only major city in the vicinity. The importance of Constantinople in the Ottoman world was also reflected by its Ottoman name ‚Der Saadet‘ meaning the ‚gate to Prosperity‘ in Ottoman. An alternative view is that the name evolved directly from the name Constantinople, with the first and third syllables dropped.[22] A Turkish folk etymology traces the name to Islam bol „plenty of Islam“[31] because the city was called Islambol („plenty of Islam“) or Islambul („find Islam“) as the capital of the Islamic Ottoman Empire. It is first attested shortly after the conquest, and its invention was ascribed by some contemporary writers to Sultan Mehmed II himself.[32] Some Ottoman sources of the 17th century, such as Evliya Çelebi, describe it as the common Turkish name of the time; between the late 17th and late 18th centuries, it was also in official use. The first use of the word „Islambol“ on coinage was in 1703 (1115 AH) during the reign of Sultan Ahmed III.[33]

In modern Turkish, the name is written as İstanbul, with a dotted İ, as the Turkish alphabet distinguishes between a dotted and dotless I. In English the stress is on the first or last syllable, but in Turkish it is on the second syllable (tan).[34] A person from the city is an İstanbullu (plural: İstanbullular), although Istanbulite is used in English.[35]

History

Neolithic artifacts, uncovered by archeologists at the beginning of the 21st century, indicate that Istanbul’s historic peninsula was settled as far back as the 6th millennium BCE.[36] That early settlement, important in the spread of the Neolithic Revolution from the Near East to Europe, lasted for almost a millennium before being inundated by rising water levels.[37][38][39][40] The first human settlement on the Asian side, the Fikirtepe mound, is from the Copper Age period, with artifacts dating from 5500 to 3500 BCE,[41] On the European side, near the point of the peninsula (Sarayburnu), there was a Thracian settlement during the early 1st millennium BCE. Modern authors have linked it to the Thracian toponym Lygos,[42] mentioned by Pliny the Elder as an earlier name for the site of Byzantium.[43]

The history of the city proper begins around 660 BCE,[44][c] when Greek settlers from Megara established Byzantium on the European side of the Bosphorus. The settlers built an acropolis adjacent to the Golden Horn on the site of the early Thracian settlements, fueling the nascent city’s economy.[50] The city experienced a brief period of Persian rule at the turn of the 5th century BCE, but the Greeks recaptured it during the Greco-Persian Wars.[51] Byzantium then continued as part of the Athenian League and its successor, the Second Athenian League, before gaining independence in 355 BCE.[52] Long allied with the Romans, Byzantium officially became a part of the Roman Empire in 73 CE.[53] Byzantium’s decision to side with the Roman usurper Pescennius Niger against Emperor Septimius Severus cost it dearly; by the time it surrendered at the end of 195 CE, two years of siege had left the city devastated.[54] Five years later, Severus began to rebuild Byzantium, and the city regained—and, by some accounts, surpassed—its previous prosperity.[55]

Rise and fall of Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire

Constantine the Great effectively became the emperor of the whole of the Roman Empire in September 324.[56] Two months later, he laid out the plans for a new, Christian city to replace Byzantium. As the eastern capital of the empire, the city was named Nova Roma; most called it Constantinople, a name that persisted into the 20th century.[57] On 11 May 330, Constantinople was proclaimed the capital of the Roman Empire, which was later permanently divided between the two sons of Theodosius I upon his death on 17 January 395, when the city became the capital of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire.[58]

The establishment of Constantinople was one of Constantine’s most lasting accomplishments, shifting Roman power eastward as the city became a center of Greek culture and Christianity.[58][59] Numerous churches were built across the city, including Hagia Sophia which was built during the reign of Justinian the Great and remained the world’s largest cathedral for a thousand years.[60] Constantine also undertook a major renovation and expansion of the Hippodrome of Constantinople; accommodating tens of thousands of spectators, the hippodrome became central to civic life and, in the 5th and 6th centuries, the center of episodes of unrest, including the Nika riots.[61][62] Constantinople’s location also ensured its existence would stand the test of time; for many centuries, its walls and seafront protected Europe against invaders from the east and the advance of Islam.[59] During most of the Middle Ages, the latter part of the Byzantine era, Constantinople was the largest and wealthiest city on the European continent and at times the largest in the world.[63][64]

Constantinople began to decline continuously after the end of the reign of Basil II in 1025. The Fourth Crusade was diverted from its purpose in 1204, and the city was sacked and pillaged by the crusaders.[65] They established the Latin Empire in place of the Orthodox Byzantine Empire.[66] Hagia Sophia was converted to a Catholic church in 1204. The Byzantine Empire was restored, albeit weakened, in 1261.[67] Constantinople’s churches, defenses, and basic services were in disrepair,[68] and its population had dwindled to a hundred thousand from half a million during the 8th century.[d] After the reconquest of 1261, however, some of the city’s monuments were restored, and some, like the two Deisis mosaics in Hagia Sofia and Kariye, were created.

Various economic and military policies instituted by Andronikos II, such as the reduction of military forces, weakened the empire and left it vulnerable to attack.[69] In the mid-14th-century, the Ottoman Turks began a strategy of gradually taking smaller towns and cities, cutting off Constantinople’s supply routes and strangling it slowly.[70] On 29 May 1453, after an eight-week siege (during which the last Roman emperor, Constantine XI, was killed), Sultan Mehmed II „the Conqueror“ captured Constantinople and declared it the new capital of the Ottoman Empire. Hours later, the sultan rode to the Hagia Sophia and summoned an imam to proclaim the Islamic creed, converting the grand cathedral into an imperial mosque due to the city’s refusal to surrender peacefully.[71] Mehmed declared himself as the new „Kaysar-i Rûm“ (the Ottoman Turkish equivalent of Caesar of Rome) and the Ottoman state was reorganized into an empire.[72]

Ottoman Empire and Turkish Republic eras

Following the conquest of Constantinople[e], Mehmed II immediately set out to revitalize the city. He urged the return of those who had fled the city during the siege, and resettled Muslims, Jews, and Christians from other parts of Anatolia. He demanded that five thousand households needed to be transferred to Constantinople by September.[74] From all over the Islamic empire, prisoners of war and deported people were sent to the city: these people were called „Sürgün“ in Turkish (Greek: σουργούνιδες).[75] Many people escaped again from the city, and there were several outbreaks of plague, so that in 1459 Mehmet allowed the deported Greeks to come back to the city.[76] He also invited people from all over Europe to his capital, creating a cosmopolitan society that persisted through much of the Ottoman period.[77] Plague continued to be essentially endemic in Constantinople for the rest of the century, as it had been from 1520, with a few years of respite between 1529 and 1533, 1549 and 1552, and from 1567 to 1570; epidemics originating in the West and in the Hejaz and southern Russia.[78] Population growth in Anatolia allowed Constantinople to replace its losses and maintain its population of around 500,000 inhabitants down to 1800. Mehmed II also repaired the city’s damaged infrastructure, including the whole water system, began to build the Grand Bazaar, and constructed Topkapı Palace, the sultan’s official residence.[79] With the transfer of the capital from Edirne (formerly Adrianople) to Constantinople, the new state was declared as the successor and continuation of the Roman Empire.[80]

The Ottomans quickly transformed the city from a bastion of Christianity to a symbol of Islamic culture. Religious foundations were established to fund the construction of ornate imperial mosques, often adjoined by schools, hospitals, and public baths.[79] The Ottoman Dynasty claimed the status of caliphate in 1517, with Constantinople remaining the capital of this last caliphate for four centuries.[14] Suleiman the Magnificent’s reign from 1520 to 1566 was a period of especially great artistic and architectural achievement; chief architect Mimar Sinan designed several iconic buildings in the city, while Ottoman arts of ceramics, stained glass, calligraphy, and miniature flourished.[81] The population of Constantinople was 570,000 by the end of the 18th century.[82]

A period of rebellion at the start of the 19th century led to the rise of the progressive Sultan Mahmud II and eventually to the Tanzimat period, which produced political reforms and allowed new technology to be introduced to the city.[83] Bridges across the Golden Horn were constructed during this period,[84] and Constantinople was connected to the rest of the European railway network in the 1880s.[85] Modern facilities, such as a water supply network, electricity, telephones, and trams, were gradually introduced to Constantinople over the following decades, although later than to other European cities.[86] The modernization efforts were not enough to forestall the decline of the Ottoman Empire.

Sultan Abdul Hamid II was deposed with the Young Turk Revolution in 1908 and the Ottoman Parliament, closed since 14 February 1878, was reopened 30 years later on 23 July 1908, which marked the beginning of the Second Constitutional Era.[87] A series of wars in the early 20th century, such as the Italo-Turkish War (1911–1912) and the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), plagued the ailing empire’s capital and resulted in the 1913 Ottoman coup d’état, which brought the regime of the Three Pashas.[88]

The Ottoman Empire joined World War I (1914–1918) on the side of the Central Powers and was ultimately defeated. The deportation of Armenian intellectuals on 24 April 1915 was among the major events which marked the start of the Armenian Genocide during WWI.[89] As a result of the war and the events in its aftermath, the city’s Christian population declined from 450,000 to 240,000 between 1914 and 1927.[90] The Armistice of Mudros was signed on 30 October 1918 and the Allies occupied Constantinople on 13 November 1918. The Ottoman Parliament was dissolved by the Allies on 11 April 1920 and the Ottoman delegation led by Damat Ferid Pasha was forced to sign the Treaty of Sèvres on 10 August 1920.

Following the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1922), the Grand National Assembly of Turkey in Ankara abolished the Sultanate on 1 November 1922, and the last Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed VI, was declared persona non-grata. Leaving aboard the British warship HMS Malaya on 17 November 1922, he went into exile and died in Sanremo, Italy, on 16 May 1926. The Treaty of Lausanne was signed on 24 July 1923, and the occupation of Constantinople ended with the departure of the last forces of the Allies from the city on 4 October 1923.[91] Turkish forces of the Ankara government, commanded by Şükrü Naili Pasha (3rd Corps), entered the city with a ceremony on 6 October 1923, which has been marked as the Liberation Day of Istanbul (Turkish: İstanbul’un Kurtuluşu) and is commemorated every year on its anniversary.[91] On 29 October 1923 the Grand National Assembly of Turkey declared the establishment of the Turkish Republic, with Ankara as its capital. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk became the Republic’s first President.[92]

Ankara was selected as Turkey’s capital in 1923 to distance the new, secular republic from its Ottoman history.[93] According to historian Philip Mansel:

- after the departure of the dynasty in 1925, from being the most international city in Europe, Constantinople became one of the most nationalistic….Unlike Vienna, Constantinople turned its back on the past. Even its name was changed. Constantinople was dropped because of its Ottoman and international associations. From 1926 the post office only accepted Istanbul; it appeared more Turkish and was used by most Turks.[94]

From the late 1940s and early 1950s, Istanbul underwent great structural change, as new public squares, boulevards, and avenues were constructed throughout the city, sometimes at the expense of historical buildings.[95] The population of Istanbul began to rapidly increase in the 1970s, as people from Anatolia migrated to the city to find employment in the many new factories that were built on the outskirts of the sprawling metropolis. This sudden, sharp rise in the city’s population caused a large demand for housing, and many previously outlying villages and forests became engulfed into the metropolitan area of Istanbul.[96]

Cityscape

The Fatih district, which was named after Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror (Turkish: Fatih Sultan Mehmed), corresponds to what was, until the Ottoman conquest in 1453, the whole of the city of Constantinople (today is the capital district and called the historic peninsula of Istanbul) on the southern shore of the Golden Horn, across the medieval Genoese citadel of Galata on the northern shore. The Genoese fortifications in Galata were largely demolished in the 19th century, leaving only the Galata Tower, to make way for the northward expansion of the city.[136] Galata (Karaköy) is today a quarter within the Beyoğlu (Pera) district, which forms Istanbul’s commercial and entertainment center and includes İstiklal Avenue and Taksim Square.[137]

Dolmabahçe Palace, the seat of government during the late Ottoman period, is in the Beşiktaş district on the European shore of the Bosphorus strait, to the north of Beyoğlu. The Sublime Porte (Bâb-ı Âli), which became a metonym for the Ottoman government, was originally used to describe the Imperial Gate (Bâb-ı Hümâyûn) at the outermost courtyard of the Topkapı Palace; but after the 18th century, the Sublime Porte (or simply Porte) began to refer to the gate of the Sadrazamlık (Prime Ministry) compound in the Cağaloğlu quarter near Topkapı Palace, where the offices of the Sadrazam (Grand Vizier) and other Viziers were, and where foreign diplomats were received. The former village of Ortaköy is within Beşiktaş and gives its name to the Ortaköy Mosque on the Bosphorus, near the Bosphorus Bridge. Lining both the European and Asian shores of the Bosphorus are the historic yalıs, luxurious chalet mansions built by Ottoman aristocrats and elites as summer homes.[138] Farther inland, outside the city’s inner ring road, are Levent and Maslak, Istanbul’s main business districts.[139]

During the Ottoman period, Üsküdar (then Scutari) and Kadıköy were outside the scope of the urban area, serving as tranquil outposts with seaside yalıs and gardens. But in the second half of the 20th century, the Asian side experienced major urban growth; the late development of this part of the city led to better infrastructure and tidier urban planning when compared with most other residential areas in the city.[10] Much of the Asian side of the Bosphorus functions as a suburb of the economic and commercial centers in European Istanbul, accounting for a third of the city’s population but only a quarter of its employment.[10] As a result of Istanbul’s exponential growth in the 20th century, a significant portion of the city is composed of gecekondus (literally „built overnight“), referring to illegally constructed squatter buildings.[140] At present, some gecekondu areas are being gradually demolished and replaced by modern mass-housing compounds.[141] Moreover, large scale gentrification and urban renewal projects have been taking place,[142] such as the one in Tarlabaşı;[143] some of these projects, like the one in Sulukule, have faced criticism.[144] The Turkish government also has ambitious plans for an expansion of the city west and northwards on the European side in conjunction with plans for a third airport; the new parts of the city will include four different settlements with specified urban functions, housing 1.5 million people.[145]

Istanbul does not have a primary urban park, but it has several green areas. Gülhane Park and Yıldız Park were originally included within the grounds of two of Istanbul’s palaces—Topkapı Palace and Yıldız Palace—but they were repurposed as public parks in the early decades of the Turkish Republic.[146] Another park, Fethi Paşa Korusu, is on a hillside adjacent to the Bosphorus Bridge in Anatolia, opposite Yıldız Palace in Europe. Along the European side, and close to the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge, is Emirgan Park, which was known as the Kyparades (Cypress Forest) during the Byzantine period. In the Ottoman period, it was first granted to Nişancı Feridun Ahmed Bey in the 16th century, before being granted by Sultan Murad IV to the Safavid Emir Gûne Han in the 17th century, hence the name Emirgan. The 47-hectare (120-acre) park was later owned by Khedive Ismail Pasha of Ottoman Egypt and Sudan in the 19th century. Emirgan Park is known for its diversity of plants and an annual tulip festival is held there since 2005.[147] The AKP government’s decision to replace Taksim Gezi Park with a replica of the Ottoman era Taksim Military Barracks (which was transformed into the Taksim Stadium in 1921, before being demolished in 1940 for building Gezi Park) sparked a series of nationwide protests in 2013 covering a wide range of issues. Popular during the summer among Istanbulites is Belgrad Forest, spreading across 5,500 hectares (14,000 acres) at the northern edge of the city. The forest originally supplied water to the city and remnants of reservoirs used during Byzantine and Ottoman times survive.[148][149]

Edge cities (office and retail districts)

Modern shopping malls, dense residential and hotel towers, and entertainment, educational and other facilities can be found outside the historic center in the following edge cities:[150]

- Taksim-Beyoğlu: Taksim Square in Beyoğlu to Nişantaşı in Şişli[150]

- The Central Business District as the real estate industry refers to it, which is not the historic city center, but is a 7-km-long north-south corridor of modern areas along Barbaros Boulevard and Büyükdere Avenue. Metro Line 2 runs along part of it. From south to north, the areas in the corridor are:[150]

- in Beşiktaş district:

- Balmumcu

- Gayrettepe incl. Profilo, Astoria and Trump Towers (Trump Alışveriş Merkezi) complexes

- Etiler including Boğaziçi University

- in Şişli district:

- Fulya, Otim and the core Şişli neighborhood incl. the İstanbul Cevahir complex

- Esentepe including Zincirlikuyu and the Zorlu Center complex

- Levent including the Metrocity, Özdilekpark, Kanyon and Istanbul Sapphire complexes

- in Sarıyer district:

- Maslak including the İstinye Park complex and the Istanbul Technical University

- the Vadistanbul mall and office complexes in Ayazağa

- in Beşiktaş district:

- Istanbul Atatürk Airport area: strip development along the O-7 highway north to the Mall of Istanbul, Bahçelievler district[150]

- Asian side:

Architecture

Early Byzantine architecture followed the classical Roman model of domes and arches, but improved upon these elements, as in the Church of the Saints Sergius and Bacchus. The oldest surviving Byzantine church in Istanbul—albeit in ruins—is the Monastery of Stoudios (later converted into the Imrahor Mosque), which was built in 454.[154] After the recapture of Constantinople in 1261, the Byzantines enlarged two of the most important churches extant, Chora Church and Pammakaristos Church. The pinnacle of Byzantine architecture, and one of Istanbul’s most iconic structures, is the Hagia Sophia. Topped by a dome 31 meters (102 ft) in diameter,[155] the Hagia Sophia stood as the world’s largest cathedral for centuries, and was later converted into a mosque and, as it stands now, a museum.[60]

Among the oldest surviving examples of Ottoman architecture in Istanbul are the Anadoluhisarı and Rumelihisarı fortresses, which assisted the Ottomans during their siege of the city.[156] Over the next four centuries, the Ottomans made an indelible impression on the skyline of Istanbul, building towering mosques and ornate palaces. The largest palace, Topkapı, includes a diverse array of architectural styles, from Baroque inside the Harem, to its Neoclassical style Enderûn Library.[157] The imperial mosques include Fatih Mosque, Bayezid Mosque, Yavuz Selim Mosque, Süleymaniye Mosque, Sultan Ahmed Mosque (the Blue Mosque), and Yeni Mosque, all of which were built at the peak of the Ottoman Empire, in the 16th and 17th centuries. In the following centuries, and especially after the Tanzimat reforms, Ottoman architecture was supplanted by European styles.[158] An example of which is the imperial Nuruosmaniye Mosque. Areas around İstiklal Avenue were filled with grand European embassies and rows of buildings in Neoclassical, Renaissance Revival and Art Nouveau styles, which went on to influence the architecture of a variety of structures in Beyoğlu—including churches, stores, and theaters—and official buildings such as Dolmabahçe Palace.[159]

Culture

Istanbul was historically known as a cultural hub, but its cultural scene stagnated after the Turkish Republic shifted its focus toward Ankara.[232] The new national government established programs that served to orient Turks toward musical traditions, especially those originating in Europe, but musical institutions and visits by foreign classical artists were primarily centered in the new capital.[233] Much of Turkey’s cultural scene had its roots in Istanbul, and by the 1980s and 1990s Istanbul reemerged globally as a city whose cultural significance is not solely based on its past glory.[234]

By the end of the 19th century, Istanbul had established itself as a regional artistic center, with Turkish, European, and Middle Eastern artists flocking to the city. Despite efforts to make Ankara Turkey’s cultural heart, Istanbul had the country’s primary institution of art until the 1970s.[235] When additional universities and art journals were founded in Istanbul during the 1980s, artists formerly based in Ankara moved in.[236] Beyoğlu has been transformed into the artistic center of the city, with young artists and older Turkish artists formerly residing abroad finding footing there. Modern art museums, including İstanbul Modern, the Pera Museum, Sakıp Sabancı Museum and SantralIstanbul, opened in the 2000s to complement the exhibition spaces and auction houses that have already contributed to the cosmopolitan nature of the city.[237] These museums have yet to attain the popularity of older museums on the historic peninsula, including the Istanbul Archaeology Museums, which ushered in the era of modern museums in Turkey, and the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum.[230][231]

The first film screening in Turkey was at Yıldız Palace in 1896, a year after the technology publicly debuted in Paris.[242] Movie theaters rapidly cropped up in Beyoğlu, with the greatest concentration of theaters being along the street now known as İstiklal Avenue.[243] Istanbul also became the heart of Turkey’s nascent film industry, although Turkish films were not consistently developed until the 1950s.[244] Since then, Istanbul has been the most popular location to film Turkish dramas and comedies.[245] The Turkish film industry ramped up in the second half of the century, and with Uzak (2002) and My Father and My Son (2005), both filmed in Istanbul, the nation’s movies began to see substantial international success.[246] Istanbul and its picturesque skyline have also served as a backdrop for several foreign films, including From Russia with Love (1963), Topkapi (1964), The World Is Not Enough (1999), and Mission Istaanbul (2008).[247]

Coinciding with this cultural reemergence was the establishment of the Istanbul Festival, which began showcasing a variety of art from Turkey and around the world in 1973. From this flagship festival came the International Istanbul Film Festival and the Istanbul International Jazz Festival in the early 1980s. With its focus now solely on music and dance, the Istanbul Festival has been known as the Istanbul International Music Festival since 1994.[248] The most prominent of the festivals that evolved from the original Istanbul Festival is the Istanbul Biennial, held every two years since 1987. Its early incarnations were aimed at showcasing Turkish visual art, and it has since opened to international artists and risen in prestige to join the elite biennales, alongside the Venice Biennale and the São Paulo Art Biennial.[249]

Leisure and entertainment

Istanbul has numerous shopping centers, from the historic to the modern. The Grand Bazaar, in operation since 1461, is among the world’s oldest and largest covered markets.[250][251] Mahmutpasha Bazaar is an open-air market extending between the Grand Bazaar and the Egyptian Bazaar, which has been Istanbul’s major spice market since 1660. Galleria Ataköy ushered in the age of modern shopping malls in Turkey when it opened in 1987.[252] Since then, malls have become major shopping centers outside the historic peninsula. Akmerkez was awarded the titles of „Europe’s best“ and „World’s best“ shopping mall by the International Council of Shopping Centers in 1995 and 1996; Istanbul Cevahir has been one of the continent’s largest since opening in 2005; Kanyon won the Cityscape Architectural Review Award in the Commercial Built category in 2006.[251] İstinye Park in İstinye and Zorlu Center near Levent are among the newest malls which include the stores of the world’s top fashion brands. Abdi İpekçi Street in Nişantaşı and Bağdat Avenue on the Anatolian side of the city have evolved into high-end shopping districts.[253][254]

Istanbul is known for its historic seafood restaurants. Many of the city’s most popular and upscale seafood restaurants line the shores of the Bosphorus (particularly in neighborhoods like Ortaköy, Bebek, Arnavutköy, Yeniköy, Beylerbeyi and Çengelköy). Kumkapı along the Sea of Marmara has a pedestrian zone that hosts around fifty fish restaurants.[255] The Princes‘ Islands, 15 kilometers (9 mi) from the city center, are also popular for their seafood restaurants. Because of their restaurants, historic summer mansions, and tranquil, car-free streets, the Prince Islands are a popular vacation destination among Istanbulites and foreign tourists.[256] Istanbul is also famous for its sophisticated and elaborately-cooked dishes of the Ottoman cuisine. Following the influx of immigrants from southeastern and eastern Turkey, which began in the 1960s, the foodscape of the city has drastically changed by the end of the century; with influences of Middle Eastern cuisine such as kebab taking an important place in the food scene. Restaurants featuring foreign cuisines are mainly concentrated in the Beyoğlu, Beşiktaş, Şişli, and Kadıköy districts.

Istanbul has active nightlife and historic taverns, a signature characteristic of the city for centuries if not millennia. Along İstiklal Avenue is the Çiçek Pasajı, now home to winehouses (known as meyhanes), pubs, and restaurants.[257] İstiklal Avenue, originally known for its taverns, has shifted toward shopping, but the nearby Nevizade Street is still lined with winehouses and pubs.[258][259] Some other neighborhoods around İstiklal Avenue have been revamped to cater to Beyoğlu’s nightlife, with formerly commercial streets now lined with pubs, cafes, and restaurants playing live music.[260] Other focal points for Istanbul’s nightlife include Nişantaşı, Ortaköy, Bebek, and Kadıköy.[261]